Experiences with Imprint

Seventy-eight years ago, Gertrude Gompers, along with her two brothers and parents, sailed to a new life. The family left the UK, where they found temporary shelter from Hitler’s reach, for a permanent home in the US.

“Experiences like that leave their imprint,” said Gompers, who, at the time, was nine years old.

Now, at 87 years old, one of the most grueling times of her life has led her to a dental care experience with a positive mark. Gompers is a patient at Rutgers School of Dental Medicine’s (RSDM) Holocaust Survivors Program, started with the generosity of Howard Drew, an RSDM faculty born to two survivors.

“I can’t tell you how incredibly lucky I feel to have been connected to Rutgers School of Dental Medicine,” said Gompers. “I’m touched by the recognition of that time. … [The Holocaust Survivors Program is] making a statement against hatred, racism, and evil by showing kindness and respect.”

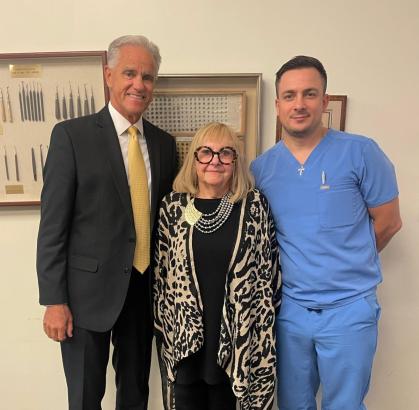

Through the program, Gompers had several procedures, including oral surgery, crowns, and a root canal treatment. Her student doctor was Igor Tomyn, under the supervision of Assistant Professor of Clinical Affairs John Moran. Said Gompers: “[Igor] has treated me with the utmost respect. He has made me feel so important, as if I were very special.”

Gompers was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1937, shortly before Hitler annexed the country. First, both of her parents lost their jobs in the fashion industry. Then, they faced increasing pressure to leave the country. But they stayed. Gompers’ mother had to scrub the streets while her father couldn’t find any employment. In this difficult time, Gompers’ grandmother took them under her wings and gave them all her money to escape to the UK when things got even tougher. Gompers’ aunt and her English husband forged bank books to show they could afford to support their relatives. “We left on November 6th, 1938,” she said. She never heard from her grandparents again. In the UK, their first stop was London. From there, they were sent to an internment camp on the Isle of Man. Following this, the family left for America as their final destination.

“We had to start all over again,” she said, in a one-bedroom apartment in New York. “We eat a lot of potatoes but were happy.” Despite being a bright student, Gompers had to join the workforce after high school and could never attend college. She first worked at a large advertising company and later got involved in politics and worked for a congressman.

Life went on looking ahead to the future until Gompers’ mother and she spoke about her grandparents—a subject that was too painful. Those conversations led Gompers to start looking back and diving into the past to write a biography. “I realized my grandparents had actually sacrificed their lives for us,” she said. Gompers discovered that both were murdered in concentration camps. These learnings pushed her to seek ways to change people’s perceptions of one another, especially of children. Her first “gig”, she said, was arranged by the Holocaust Museum of Philadelphia in the aftermath of the city’s 1985 bombing. She spoke at a neighborhood school. “I started telling them about my experiences, and they were crying,” she recounted. “They hugged and kissed me, not because they loved me, but because they felt their pain.”

She continues this mission of talking about unity. “Because, like the students I speak to … that bridges many gaps.”