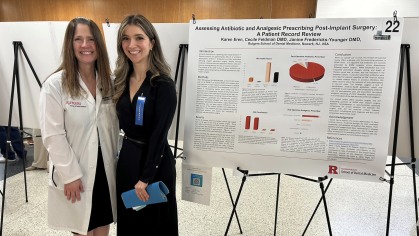

Faculty Member Explores Link Between WWI Facial Trauma and Modern Plastic Surgery

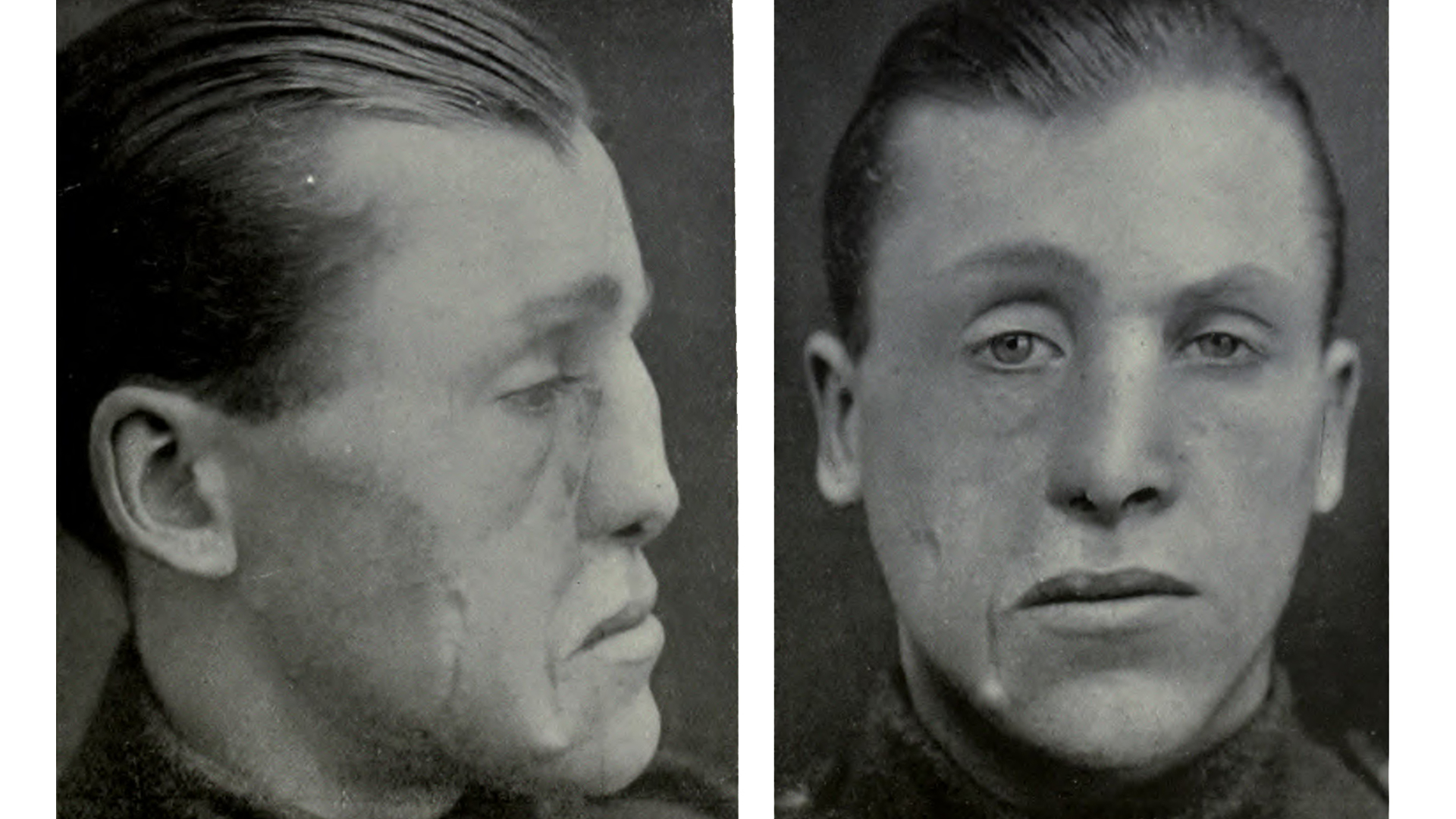

World War I veteran and plastic surgery patient

World War I veteran and plastic surgery patient

Dr. Shahid Aziz has spent hours poring over the case histories of World War I soldiers who returned home with disfiguring facial injuries.

“The world had never seen this type of injury on such a large scale,’’ said Aziz, a professor of oral and maxillofacial surgeon at the Rutgers School of Dental Medicine, who treats many facial trauma patients. “Because this was trench warfare, the head was exposed, and many of the injuries occurred to the face.’’

The danger of the trenches is portrayed in the Oscar-nominated film "1917,'' which depicts the brutality of the war. The battles, which spanned four years, claimed the lives of 40 million soldiers and left 20 million injured. Peter Jackson, who directed the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy, also focused attention on WWI with his acclaimed documentary, "They Shall Not Grow Old,'' which colorized 100-year-old footage to provide audiences with a visceral connection to history. The film, which included images of facial trauma, was released late last year after airing on the BBC.

Facial injuries took a horrible social and psychological toll on veterans, but modern-day plastic surgery was born as a result. Doctors invented new techniques to repair the damage. The practices of stabilizing fractures through the use of wires and methods of reducing cheekbone fractures were among the innovations.

“Because there was such a volume of injuries, it laid down the foundations for facial reconstructions and created new ways of thinking about how to handle them,’’ observed Aziz. “Anesthesia for facial trauma evolved. New instrumentation was designed. Some of the techniques we’re still using today.’’

The evolution of the field during WWI was international. In Great Britain, pioneering plastic surgeon Dr. Harold Gillies helped establish a hospital devoted to treating facial injuries. Most of the patients were soldiers. German plastic surgeons also achieved breakthroughs, according to Aziz.

Aziz, who has published papers on the subject and has lectured internationally, became interested in WWI as a student at Harvard Dental School, where the dental history museum displayed casts of soldiers who suffered facial injuries. They belonged to alumnus Dr. Varaztad H. Kazanjian, one of the founders of modern plastic surgery, who was head of the Harvard dental unit, which was stationed on the front lines in France during WWI.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the history of maxillofacial surgery,’’ said Aziz. “There’s a huge dental component in dealing with trauma.’’

In addition to learning about medical histories, Aziz read letters from injured soldiers. “Just studying the medical end, it can take you away from the personal side of things. Reading the leaders, you really realize the impact this had. They were young men, only 18, 19 or 20. They had to return home with significant deformities and a long road to recovery ahead of them.’’

Aziz hopes to some day write a book on the subject. But simply learning about the history has helped make him a better surgeon, he believes. “I always felt you need to learn about the past to move forward.’’